Eyenovia (NASDAQ:EYEN) is using its unique microdose drug delivery technology, Optejet, to build a late-stage pipeline of ophthalmic therapeutics.

“We have three late-stage programs for three major indications that we are advancing at the same time, which is pretty good for a company of only 30 people,” Eyenovia’s president, CMO and CEO, Dr. Sean Ianchulev, says in an interview with BioTuesdays.

Dr. Ianchulev, who is also a professor of ophthalmology and director of ophthalmic innovation and technology at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine in New York, helped develop some of the most innovative ophthalmic drugs and technologies, including Lucentis – a monoclonal antibody-based therapeutic approved for the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema – and a micro-stent for the treatment of glaucoma.

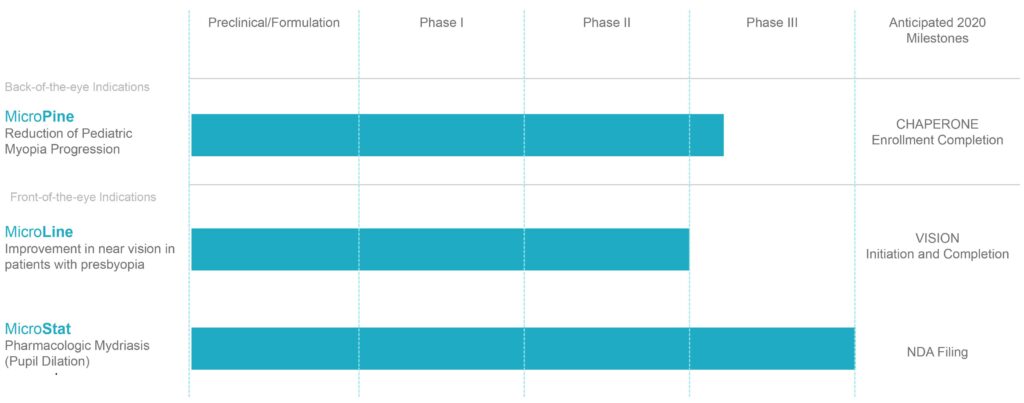

Multiple Late Stage Clinical Assets

“Eyedrop technology hasn’t changed since it was first developed more than a century ago,” Dr. Ianchulev points out. “The eye can only hold seven microliters of fluid, yet the average eye drop is 40 microliters. More importantly, eyedrops are often administered incorrectly, resulting in inappropriate dosing more than 50% of the time.”

Conventional eye drops may overdose the ocular surface, both with active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and preservatives, by as much as 300%. In addition to causing local side effects such as eye irritation, the excess fluid typically drains into the tear duct, resulting in systemic absorption of API and preservatives, which can be detrimental, he points out.

Eyedroppers are also an unreliable drug delivery system. Multiple studies have shown that patients using a standard eyedropper successfully administered the eyedrop, on the first attempt, less than half of the time. More than half of the time, patients accidentally touched the eye surface, resulting in cross-contamination.

Eyenovia’s Optejet device is a novel microdosing spray technology designed for optimal ophthalmic drug delivery. “You could say that we’ve ‘shrunk’ the inkjet printer,” Dr. Ianchulev says. “Optejet prints microdrops onto the surface of the eye, which can decrease drug and preservative exposure by about 75%.”

In addition to enabling horizontal drug delivery via a spray that is delivered before a patient has the chance to blink, Optejet is also bluetooth enabled, which can monitor patient use and send patient reminders.

In Eyenovia studies, patients using the Optejet successfully administered the microdose, on the first attempt, nearly 90% of the time, and none of the patients touched the ocular surface with the device.

Eyenovia has validated Optejet in three Phase 2 and two Phase 3 studies, which confirmed the technology’s microdosing efficacy, decreased systemic drug exposure and improved ocular tolerability.

The company is currently applying the Optejet technology to three ophthalmic indications: progressive myopia, presbyopia and mydriasis. All of Eyenovia’s clinical programs are therapeutic indications that follow the 505 (b)(2) NDA registration pathway. The Optejet micro-array print delivery platform is not regulated as a medical device or drug-device combination, which streamlines the therapeutic registration process.

Progressive myopia is a back-of-the-eye disease characterized by pathologic elongation of the eye’s sclera and retina, which causes severe visual impairment and can result in retinal detachment and myopic retinopathy. Affecting some five million Americans, the disease mostly occurs in young adults and children, with an estimated 9% of U.S. children affected. There are currently no approved drug therapies to treat progressive myopia.

“Progressive myopia is very different from the typical nearsightedness that can be corrected with glasses,” Dr. Ianchulev explains, adding that the addressable market for treating this condition is worth some $5-billion.

Progressive myopia is currently treated with hard contact lenses. Some physicians will also use non-FDA approved compounded atropine, a drug that is commonly used to reduce muscle spasms and fluid secretions in patients undergoing surgery. Low doses of atropine have been shown to slow myopia progression by at least 60%, but it is not shelf stable and often not well-tolerated, nor is it covered by third party medical insurance due to the lack of FDA-approved formulations.

“Based on several large randomized controlled studies by collaborative groups, the American Academy of Ophthalmology has indicated that Level 1 evidence supports the use of atropine to prevent myopic progression,” Dr. Ianchulev says.

MicroPine, Eyenovia’s proprietary microdose formulation of atropine, is currently in a Phase 3 trial, called CHAPERONE, for the treatment of progressive myopia, with a primary endpoint of the change in myopia progression from baseline through 36 months. The trial is still enrolling patients, with a target enrollment of approximately 500 children aged five-to-13. Dr. Ianchulev says that Eyenovia expects some delay in enrollment due to COVID-19, but hopes to complete enrollment in nine-to-12 months.

Eyenovia is also developing MicroLine, a proprietary microdose formulation of pilocarpine, for the treatment of presbyopia, or farsightedness. Affecting almost all adults aged 40 and older, presbyopia is the age-related progressive loss of the ability to focus on nearby objects, and is most easily resolved with the use of reading glasses.

Pilocarpine, a cholinergic drug, has demonstrated the ability to temporarily extend depth-of-focus: a single microdose of the drug can improve near-range vision for three-to-four hours.

“This is a lifestyle therapeutic approach for active individuals – it’s essentially on-demand presbyopia correction. While MicroLine wouldn’t be eligible for reimbursement, we estimate that 40% of people who could use MicroLine have adequate disposable income to pay for it, which represents an addressable market of $2-billion,” Dr. Ianchulev contends.

Eyenovia hopes to initiate two identical Phase 3 trials of MicroLine, called VISION-1 and VISION-2, as soon as clinical investigator activities normalize after the COVID-19 pandemic. “We don’t expect any issues with enrollment once we get going as there are 113 million presbyopes in the U.S. alone,” he says.

The company’s most advanced program, called MicroStat, is for pharmacologic mydriasis, or the dilation of the eye that is part of a comprehensive eye exam. Every year in the U.S., some 84 million dilations are performed during eye exams or ophthalmic surgeries. Currently, pharmacologic mydriasis is achieved by administering a drop each of tropicamide and phenylephrine to dilate the pupil. Because these drugs cause stinging, a drop of anaesthetic is often administered first.

MicroStat is the first combination microdose of tropicamide and phenylephrine. Because the dosage delivered by the Optejet device is a fraction of what is currently administered, the anesthetic is unnecessary: only one of 131 patients in Eyenovia’s Phase 3 studies reported stinging.

“Physicians are currently paying more than $1.00 a patient for the two to three drops used for mydriasis, which is something they perform multiple times per day. We can provide MicroStat at the same cost, with the goal of enabling a modernized and more efficient eye exam,” he contends.

In a Phase 3 study, MicroStat enabled prompt mydriasis with efficacy superior to its single-agent components. Eyenovia plans to file an NDA for MicroStat this year. “As our most advanced program, MicroStat has the potential to validate our Optejet delivery platform for our MicroPine and MicroLine programs, as well as for additional ophthalmic indications we plan to explore in the future,” says Dr. Ianchulev.

• • • • •

To connect with Eyenovia or any of the other companies featured on BioTuesdays, send us an email at [email protected].