EyeGate Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ:EYEG) is developing a non-invasive drug delivery platform that uses an electrical process, known as iontophoresis, to deliver a corticosteroid to the front-and back-of-the-eye for the treatment of ophthalmic conditions, such as anterior uveitis, macular edema and post-cataract surgery inflammation.

“Our EyeGate II Delivery System addresses two of the most prevalent issues in ophthalmic care: the existing lack of patient compliance with eye drops and patient safety from the use of intravitreal injections,” president and CEO, Stephen From, says in an interview with BioTuesdays.com.

EyeGate, which went public 11 months ago, signed an exclusive, worldwide licensing agreement last summer with the Bausch & Lomb subsidiary of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International (NYSE, TSX:VRX) for its EGP-437 corticosteroid in the field of uveitis, as well as a right of last negotiation to license the product for other indications.

Uveitis is an inflammation of the uvea tract at the front-of-the-eye. Non-infectious anterior uveitis is the most common form of uveitis, with an incidence in the U.S. of approximately 26-to-102 people per 100,000 annually. Non-compliance with eye drops can lead to sight-threatening complications.

“This is a small target market but an ideal indication to demonstrate the power of our platform, so a great entre to get into the clinic,” Mr. From contends. “The bigger market opportunities are macular edema and cataract surgery.”

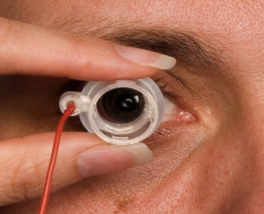

Mr. From explains that iontophoresis involves applying an electrical current to an ionizable substance – one capable of carrying an electric charge – to increase its mobility across a biological membrane and, through electro-repulsion, drive a like-charged drug substance into the ocular tissue.

As part of the treatment, an electrode is attached to the forehead of a patient. An optometrist or ophthalmologist would fill the device applicator with the drug and set both the dosage and current on the device.

The physician then applies a small electrical current from the device to the electrode on the applicator. Electrolysis of water molecules occurs at the surface of the electrode in the applicator, which exerts electro-repulsion on the drug molecules, driving them into the ocular tissues until they reach either the front or the back of the eye. The treatment takes only a few minutes.

EyeGate’s non-invasive drug delivery platform uses an electrical process, known as iontophoresis, to deliver a corticosteroid to the front-and back-of-the-eye for the treatment of ophthalmic conditions.

“We use one concentration of drug and change the dose by changing the current and application time,” he adds.

EGP-437 incorporates a reformulated topically active corticosteroid, dexamethasone phosphate. Mr. From says EyeGate has conducted more than 1,700 treatments with the drug delivery platform, of which more than 1,000 have been with EGP-437.

In an initiation report in November, Maxim Group analyst, Jason Kolbert, wrote that EyeGate is at the forefront of ophthalmic innovation and is leading the movement towards safer, easier-to-administer treatments for ophthalmic conditions.

“In addition to safety and ease of administration, these therapeutic candidates have the potential for efficacy, onset of action, and sustained therapeutic effects that are superior to the current standard of care,” he added.

He rates the stock at “buy” with a 12-month price target of $11. The stock closed at $1.74 on Friday.

EyeGate has completed one Phase 3 pivotal trial of EGP-437 for the treatment of non-infectious anterior uveitis, and plans to initiate a confirmatory Phase 3 trial this month.

According to EyeGate, electrolysis of water molecules occurs at the surface of the electrode in the applicator, which exerts electro-repulsion on the drug molecules, driving them into the ocular tissues.

In the initial Phase 3 study, with 193 moderate-to-severe anterior uveitis patients, EGP-437 successfully achieved the same response rate as standard-of-care eye drops, prednisolone acetate 1%.

However, patients in the control arm required 154 eye drops to achieve the primary endpoint of total clearing of white blood cells in the anterior chamber of the eye, compared with two treatments of iontophoretic EGP-437.

Patients in the EGP-437 treatment arm also had a significantly lower incidence of increased intraocular pressure, compared with the control group. The condition also was more transient in the treatment arm. The longer increased intraocular pressure persists, the greater the chance of vision damage and vision loss.

“Ophthalmologists are cautious on dosing of steroids prescribed to patients with anterior uveitis because of potential problems with increased intraocular pressure,” Mr. From points out.

While EyeGate is responsible for development of anterior uveitis in the U.S., Valeant will be responsible for development outside the U.S.

The second Phase 3 trial expects to enroll 250 patients with anterior uveitis over the next 10-to-12 months. The primary endpoint is the same as the first trial: zero white blood cell count at day 14. EyeGate plans to add a third treatment of EGP-437 in hopes of showing superiority over eye drops in the control arm.

If the trial is successful, Mr. From figures the company would be in a position to file a NDA with the FDA in mid-2017.

Last November, EyeGate reported positive interim data from a Phase 1/2a clinical trial on the effects of iontophoretic delivery of EGP-437 ophthalmic solution on macular edema patients.

Macular edema is an abnormal thickening of macula associated with accumulation of excess fluid in the extracellular space of neurosensory retina cells and is considered a leading cause of central vision loss in the developed world.

Uveitis is an inflammation of the uvea tract at the front-of-the-eye. Non-compliance with eye drops can lead to sight-threatening complications.

The trial enrolled 19 patients with three types of macular edema: retinal vein occlusion, diabetic retinopathy and post-surgical (cystoid) macular edema.

Mr. From says the interim data from the study suggests that iontophoresis can non-invasively deliver EGP-437 to the back-of-the-eye, demonstrating a positive response in some patients with macular edema.

Specifically, he notes that some patients with pseudophakic eyes, or those implanted with an intraocular lens after cataract surgery, responded better than people than phakic eyes, or those with a natural lens.

In addition, there was no increase in ocular pressure even at three times the iontophoretic dose that was used for the company’s Phase 3 non-infectious anterior uveitis trial.

An extension phase of the trial will recruit an additional 15 patients, with a modified dosing regimen and data expected in mid-2016. The extension will also evaluate the efficacy of iontophoretic EGP-437 in phakic versus pseudophakic eyes to collect additional data on the response differences of both types of eyes. The data will be helpful in designing further clinical trials, he adds.

Mr. From says iontophoresis as an in-office treatment has multiple reimbursement codes, including J-Code for the cost of the drug and disposable kit and CPT Code for performing the treatment. “Our treatment can be administered by an optometrist, which would represent a new revenue stream for them.”

EyeGate also is working with a collaborator to develop a new version of its drug delivery platform for home use.

“We are trying to miniaturize the electronics and put it into a contact lens that also would have drug added to it,” he explains. “The idea would be to wirelessly charge the lens for home use to deliver drug to the back-of-the-eye for the treatment of macular degeneration. Patients at home would use it once-or-twice-a-week as an alternative to intravitreal injections.”

EyeGate hopes to have animal proof-of-concept data by the end of the current quarter.